Silence for the monks is a rule of life. It protects them from uncontrollable and unrestrained talk as well as from impugnation and slander, which result in the death of the soul. It delivers them from wrangle and strife and preserves in them internal peace which is necessary for inwardness. Silence is the fruit of quietude, an internal state which gives birth to spiritual discourse.

-When does the monk ought to keep quiet and when does he ought to talk?

Abbot Pimen offers a solution to the issue with great discernment: “A brother asked Abbot Pimen saying: ‘which is best: to talk or to keep quiet?’And the Elder tells him: ‘Whoever talks for the sake of God, does well. Whoever keeps quiet for the sake of God, does equally well’”.

Silence is not the goal but the means. One uses it either to approach God or to talk about Him.

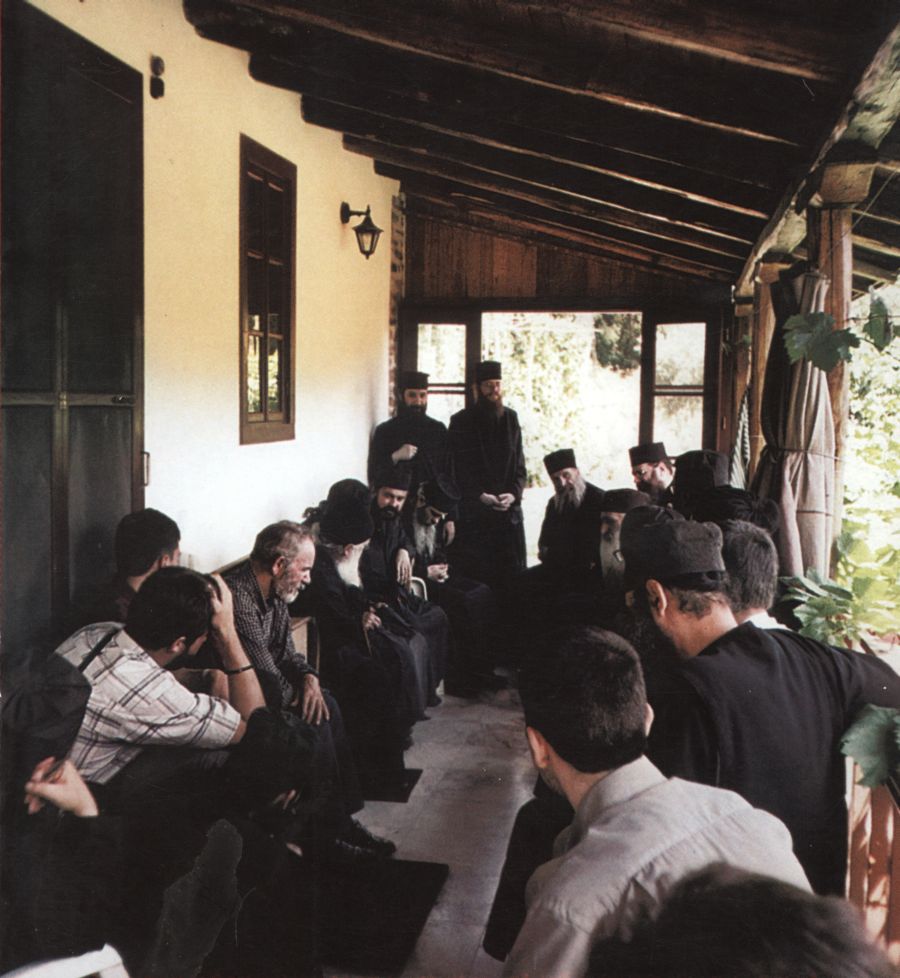

The Elders, those old warriors and much experienced strugglers in the spiritual arena, are forced to become spiritual teachers and coaches for those Christians who approach them either out of curiosity, or interest, or because of a deeper spiritual need. They fire at them demanding questions on serious and basic spiritual issues. “Father, tell me something. How can I be saved? Give me a word! What shall I do about my passions? Give me a command and I will obey! To what shall I adhere in order to please God?”

Often the Elders give a brief, general reply like an apothegm. Their words are not philosophical- i.e. the result of an intellectual process. They are ripe and full of pain, direct, forceful and without frills, which pierce the internal depths of the soul of the inquirer.

They use simple words, without adorned intellectual rhetoric; they reveal the hidden treasure of spiritual life and hand out messages which are always contemporary. Thus, they become beacons to those who are wrangling in the dark seas of confusion and delusion.

The Elders- humble, unknown and undetected ascetics- penetrate the souls of their interlocutors with discernment and their replies are in accordance to their real needs. The purpose of their talk is “such as is good for building up, as fits the occasion, that it may give grace to those who hear” (Ephesians 4, 29).

They avoid replying to inquiries if those who ask are able to see their deeds and their example. Once, when a brother asked Abbot Sisoeh: “Tell me something”, he replied: “Why do you force me to engage in idle talk? Do as you see.”

The words which come out of the Elders’ mouths are practical and have practical aims- to assist in the attainment of perfection and sanctification “in Christ”. They are words filled with love. As one may discern from the tradition of the Church, the Elders confess that “this give and take is a matter of love to me”. The practical implementation of the most crucial virtue, that of love, has created the term “act lovingly” («ποιείν αγάπην») for monasticism.

When Abbot Theodore of Thermis approached Abbot Pamvo to ask for counsel, he replied: “Go and show mercy to everyone, since mercy has found favor in the face of the Lord”.

In the first part of this book, our most holy Elder Joseph, moved by sheer love, has written the replies to the queries and worries posed by our cherished visitors. In the second part, which is titled “Philokaliko Apanthisma” we have translated into Modern Greek short excerpts from passages from the book of Philokalia and the Fathers of the Church, which are relevant to the questions posed.

We wish that this book assists those devout brothers, who are engaged in the spiritual struggle while still in the outside world, to accomplish sanctification without which “no one will see God”.

The Abbot of the Great and Holy Monastery of Vatopedi,

Archimandrite Efrem

Sunday of the Myrrh bearing women, 2003

*** Excerpts from the book ‘Discourse on Mount Athos’ by Elder Joseph of Vatopedi.

http://agapienxristou.blogspot.ca/2013/08/silence-for-monks-is-rule-of-life-elder.html

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.