Friday, August 28, 2015

Commentary of St. John Chrysostom on the Beheading of the Precious Forerunner

Salome holding the plate with the Precious Head of the Forerunner of Christ Commentary of St. John Chrysostom on the Beheading of the Precious Forerunner (Matthew 14:1-12)

2. “At that time Herod the tetrarch heard of the fame of Jesus.” (Matt. xiv. 1). For Herod the king, this man’s father, he that slew the children, was dead.

But not without a purpose doth the evangelist signify the time, but to make thee observe also the haughtiness of the tyrant, and his thoughtlessness, in that not at the beginning did he inform himself about Christ, but after a very long time. For such are they that are in places of power, and are encompassed with much pomp, they learn these things late, because they do not make much account of them.

But mark thou, I pray thee, how great a thing virtue is, that he was afraid of him even when dead, and out of his fear he speaks wisely even concerning a resurrection.

“For he said,” it is mentioned, “unto his servants, This is John, whom I slew, he is risen from the dead, and therefore the mighty powers do work in him.” (Matt. xiii. 2). Seest thou the intensity of his fear? for neither then did he dare to publish it abroad, but he still speaks but to his own servants.

But yet even this opinion savored of the soldier, and was absurd. For many besides had risen from the dead, and no one had wrought anything of the kind. And his words seem to me to be the language both of vanity, and of fear. For such is the nature of unreasonable souls, they admit often a mixture of opposite passions.

But Luke affirms that the multitudes said, “This is Elias, or Jeremias, or one of the old prophets,” (Luke ix.) but he, as uttering forsooth something wiser than the rest, made this assertion.

But it is probable that before this, in answer to them that said He was John (for many had said this too), he had denied it, and said, “I slew him,” priding himself and glorying in it. For this both Mark and Luke report that he said, “John I beheaded.” (Mark vi. 16). But when the rumor prevailed, then he too saith the same as the people.

Then the evangelist relates to us also the history. And what might his reason be for not introducing it as a subject by itself? Because all their labor entirely was to tell what related to Christ, and they made themselves no secondary work besides this, except it were again to contribute to the same end. Therefore neither now would they have mentioned the history were it not on Christ’s account, and because Herod said, “John is risen again.”

But Mark saith, that Herod exceedingly honored the man, and this, when reproved. (Mark vi. 20.) So great a thing is virtue.

Then his narrative proceeds thus: “For Herod had laid hold on John, and bound him, and put him in prison, for Herodias’ sake, his brother Philip’s wife. For John said unto him, It is not lawful for thee to have her. And when he would have put him to death, he feared the people, because they counted him as a prophet.” (Matt. xiii. 3–5.)

And wherefore doth he not address his discourse at all to her, but to the man? Because it depended more on him.

But see how inoffensive he makes his accusation, as relating a history rather than bringing a charge.

4. “But when Herod’s birth-day was kept,” saith he, “the daughter of Herodias danced before them, and pleased Herod.” (Matt. xiii. 6). O diabolical revel! O satanic spectacle! O lawless dancing! and more lawless reward for the dancing. For a murder more impious than all murders was perpetrated, and he that was worthy to be crowned and publicly honored, was slain in the midst, and the trophy of the devils was set on the table.

And the means too of the victory were worthy of the deeds done. For, “The daughter of Herodias,” it is said, “danced in the midst, and pleased Herod. Whereupon he swore with an oath to give her whatsoever she would ask. And she being before instructed of her mother, said, Give me here John Baptist’s head in a charger.” (Matt. xiii. 6–8.)

Her reproach is twofold; first, that she danced, then that she pleased him, and so pleased him, as to obtain even murder for her reward.

Seest thou how savage he was? how senseless? how foolish? in putting himself under the obligation of an oath, while to her he gives full power over her request. But when he saw the evil actually ensuing, “he was sorry,” (Matt. Xiii. 9.) it is said; and yet in the first instance he had put him in bonds. Wherefore then is he sorry? Such is the nature of virtue, even amongst the wicked admiration and praises are its due. But alas for her madness! When she too ought to admire, yea, to bow down to him, for trying to redress her wrong, she on the contrary even helps to arrange the plot, and lays a snare, and asks a diabolical favor.

But he was afraid “for the oath’s sake,” it is said, “and them that sat at meat with him.” And how didst thou not fear that which is more grievous? Surely if thou wast afraid to have witnesses of thy perjury, much more oughtest thou to fear having so many witnesses of a murder so lawless.

But as I think many are ignorant of the grievance itself, whence the murder had its origin, I must declare this too, that ye may learn the wisdom of the lawgiver. What then was the ancient law, which Herod indeed trampled on, but John vindicated? The wife of him that died childless was to be given to his brother. (Deut. xxv. 5.) For since death was an incurable ill, and all was contrived for life’s sake; He makes a law that the living brother should marry her, and should call the child that is born by the name of the dead, so that his house should not utterly perish. For if the dead were not so much as to leave children, which is the greatest mitigation of death, the sorrow would be without remedy. Therefore you see, the lawgiver devised this refreshment for those who were by nature deprived of children, and commanded the issue to be reckoned as belonging to the other.

But when there was a child, this marriage was no longer permitted. “And wherefore?” one may say, “for if it was lawful for another, much more for the brother.” By no means. For He will have men’s consanguinity extended, and the sources multiplied of our interest in each other.

Why then, in the case also of death without offspring, did not another marry her? Because it would not so be accounted the child of the departed; but now his brother begetting it, the fiction became probable. And besides, any other man had no constraining call to build up the house of the dead, but this had incurred the claim by relationship.

Forasmuch then as Herod had married his brother’s wife, when she had a child, therefore John blames him, and blames him with moderation, showing together with his boldness, his consideration also.

But mark thou, I pray thee, how the whole theatre was devilish. For first, it was made up of drunkenness and luxury, whence nothing healthful could come. Secondly, the spectators in it were depraved, and he that gave the banquet the worst transgressor of all. Thirdly, there was the irrational pleasure. Fourthly, the damsel, because of whom the marriage was illegal, who ought even to have hid herself, as though her mother were dishonored by her, comes making a show, and throwing into the shade all harlots, virgin as she was.

And the time again contributes no little to the reproof of this enormity. For when he ought to be thanking God, that on that day He had brought him to light, then he ventures upon those lawless acts. When one in chains ought to have been freed by him, then he adds slaughter to bonds.

Hearken, ye virgins, or rather ye wives also, as many as consent to such unseemliness at other person’s weddings, leaping, and bounding, and disgracing our common nature. Hearken, ye men too, as many as follow after those banquets, full of expense and drunkenness, and fear ye the gulf of the evil one. For indeed so mightily did he seize upon that wretched person just then, that he sware even to give the half of his kingdom: this being Mark’s statement, “He sware unto her, Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, I will give it thee, unto the half of my kingdom.” (Mark vi. 23.)

Such was the value he set upon his royal power; so was he once for all made captive by his passion, as to give up his kingdom for a dance. vilifying, reviling, insulting. But not so the saints; they on the contrary mourn for such as sin, rather than curse them.

8. This then let us also do, and let us weep for Herodias, and for them that imitate her. For many such revels now also take place, and though John be not slain, yet the members of Christ are, and in a far more grievous way. For it is not a head in a charger that the dancers of our time ask, but the souls of them that sit at the feast. For in making them slaves, and leading them to unlawful loves, and besetting them with harlots, they do not take off the head, but slay the soul, making them adulterers, and effeminate, and whoremongers.

For thou wilt not surely tell me, that when full of wine, and drunken, and looking at a woman who is dancing and uttering base words, thou dost not feel anything towards her, neither art hurried on to profligacy, overcome by thy lust. Nay, that awful thing befalls thee, that thou “makest the members of Christ members of an harlot.” (1 Cor. vi. 15.)

For though the daughter of Herodias be not present, yet the devil, who then danced in her person, in theirs also holds his choirs now, and departs with the souls of those guests taken captive.

But if ye are able to keep clear of drunkenness, yet are ye partakers of another most grievous sin; such revels being also full of much rapine. For look not, I pray thee, on the meats that are set before them, nor on the cakes; but consider whence they are gathered, and thou wilt see that it is of vexation, and covetousness, and violence, and rapine.

“Nay, ours are not from such sources,” one may say. God forbid they should be: for neither do I desire it. Nevertheless, although they be clear of these, not even so are our costly feasts freed from blame. Hear, at all events, how even apart from these things the prophet finds fault with them, thus speaking, “Woe to them that drink wine racked off, and anoint themselves with the chief ointments.” (Amos vi. 6, LXX.) Seest thou how He censures luxury too? For it is not covetousness which He here lays to their charge, but prodigality only.

And thou eatest to excess, Christ not even for need; thou various cakes, He not so much as dry bread; thou drinkest Thasian wine, but on Him thou hast not bestowed so much as a cup of cold water in His thirst. Thou art on a soft and embroidered bed, but He is perishing with the cold.

Wherefore, though the banquets be clear from covetousness, yet even so are they accursed, because, while for thy part thou doest all in excess, to Him thou givest not even His need; and that, living in luxury upon things that belong to Him. Why, if thou wert guardian to a child, and having taken possession of his goods, were to neglect him in extremities, thou wouldest have ten thousand accusers, and wouldest suffer the punishment appointed by the laws; and now having taken possession of the goods of Christ, and thus consuming them for no purpose, dost thou not think thou wilt have to give account?

9. And these things I say not of those who introduce harlots to their tables (for to them I have nothing to say, even as neither have I to the dogs), nor of those who cheat some, and pamper others (for neither with them have I anything to do, even as I have not with the swine and with the wolves); but of those who enjoy indeed their own property, but do not impart thereof to others; of those who spend their patrimony at random. For neither are these clear from reprehension. For how, tell me, wilt thou escape reproving and blame, while thy parasite is pampered, and the dog that stands by thee, but Christ’s worth appears to thee even not equal to theirs? when the one receives so much for laughter’s sake, but the other for the Kingdom of Heaven not so much as the smallest fraction thereof. And while the parasite, on saying something witty, goes away filled; this Man, who hath taught us, what if we had not learnt we should have been no better than the dogs,—is He counted unworthy of even the same treatment with such an one?

Dost thou shudder at being told it? Shudder then at the realities. Cast out the parasites, and make Christ to sit down to meat with thee. If He partake of thy salt, and of thy table, He will be mild in judging thee: He knows how to respect a man’s table. Yea, if robbers know this, much more the Lord. Think, for instance, of that harlot, how at a table He justified her, and upbraids Simon, saying, “Thou gavest me no kiss.” (Luke vii. 54.) I say, if He feed thee, not doing these things, much more will He reward thee, doing them. Look not at the poor man, that he comes to thee filthy and squalid, but consider that Christ by him is setting foot in thine house, and cease from thy fierceness, and thy relentless words, with which thou art even aspersing such as come to thee, calling them impostors, idle, and other names more grievous than these.

And think, when thou art talking so, of the parasites; what kind of works do they accomplish? in what respect do they profit thine house? Do they really make thy dinner pleasant to thee? pleasant, by their being beaten and saying foul words? Nay, what can be more unpleasing than this, when thou smitest him that is made after God’s likeness, and from thine insolence to him gatherest enjoyment for thyself, making thine house a theatre, and filling thy banquet with stage-players, thou who art well born and free imitating the actors with their heads shaven?

These things then dost thou call pleasure, I pray thee, which are deserving of many tears, of much mourning and lamentation? And when it were fit to urge them to a good life, to give timely advice, dost thou lead them on to perjuries, and disorderly language, and call the thing a delight? and that which procures hell, dost thou account a subject of pleasure? Yea, and when they are at a loss for witty sayings, they pay the whole reckoning with oaths and false swearing. Are these things then worthy of laughter, and not of lamentations and tears? Nay, who would say so, that hath understanding?

And this I say, not forbidding them to be fed, but not for such a purpose. Nay, let their maintenance have the motive of kindness, not of cruelty; let it be compassion, not insolence. Because he is a poor man, feed him; because Christ is fed, feed him; not for introducing satanical sayings, and disgracing his own life. Look not at him outwardly laughing, but examine his conscience, and then thou wilt see him uttering ten thousand imprecations against himself, and groaning, and wailing. And if he do not show it, this also is due to thee.

10. Let the companions of thy meals then be men that are poor and free, not perjured persons, nor stage-players. And if thou must needs ask of them a requital for their food, enjoin them, should they see anything done that is amiss, to rebuke, to admonish, to help thee in thy care over thine household, in the government of thy servants. Hast thou children? Let these be joint fathers to them, let them divide thy charge with thee, let them yield thee such profits as God loveth. Engage them in a spiritual traffic. And if thou see one needing protection, bid them succor, command them to minister. By these do thou track the strangers out, by these clothe the naked, by these send to the prison, put an end to the distresses of others.

Let them give thee, for their food, this requital, which profits both thee and them, and carries with it no condemnation.

Hereby friendship also is more closely riveted. For now, though they seem to be loved, yet for all that they are ashamed, as living without object in thy house; but if they accomplish these purposes, both they will be more pleasantly situated, and thou wilt have more satisfaction in maintaining them, as not spending thy money without fruit; and they again will dwell with thee in boldness and due freedom, and thy house, instead of a theatre, will become to thee a church, and the devil will be put to flight, and Christ will enter, and the choir of the angels. For where Christ is, there are the angels too, and where Christ and the angels are, there is Heaven, there is a light more cheerful than this of the sun.

And if thou wouldest reap yet another consolation through their means, command them, when thou art at leisure, to take their books and read the divine law. They will have more pleasure in so ministering to you, than in the other way. For these things add respect both to thee and to them, but those bring disgrace upon all together; upon thee as an insolent person and a drunkard, upon them as wretched and gluttonous. For if thou feed in order to insult them, it is worse than if thou hadst put them to death; but if for their good and profit, it is more useful again than if thou hadst brought them back from their way to execution. And now indeed thou dost disgrace them more than thy servants, and thy servants enjoy more liberty of speech, and freedom of conscience, than they do; but then thou wilt make them equal to the angels.

Set free therefore both them and thine own self, and take away the name of parasite, and call them companions of thy meals; cast away the appellation of flatterers, and bestow on them that of friends. With this intent indeed did God make our friendships, not for evil to the beloved and loving, but for their good and profit.

But these friendships are more grievous than any enmity. For by our enemies, if we will, we are even profited; but by these we must needs be harmed, no question of it. Keep not then friends to teach thee harm; keep not friends who are enamored rather of thy table than of thy friendship. For all such persons, if thou retrench thy good living, retrench their friendship too; but they that associate with thee for virtue’s sake, remain continually, enduring every change.

And besides, the race of the parasites doth often take revenge upon thee, and bring upon thee an ill fame. Hence at least I know many respectable persons to have got bad characters, and some have been evil reported of for sorceries, some for adulteries and corrupting of youths. For whereas they have no work to do, but spend their own life unprofitably; their ministry is suspected by the multitude as being the same with that of corrupt youths.

Therefore, delivering ourselves both from evil report, and above all from the hell that is to come, and doing the things that are well-pleasing to God, let us put an end to this devilish custom, that “both eating and drinking we may do all things to the glory of God,” (1 Cor. x. 31) and enjoy the glory that cometh from Him; unto which may we all attain, by the grace and love towards man of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory and might, now and ever, and world without end. Amen.

Apolytikion of St. John the Forerunner in the Second Tone

The memory of the just is observed with hymns of praise; for you suffices the testimony of the Lord, O Forerunner. You have proved to be truly more venʹrable than the Prophets, since you were granted to baptize in the river the One whom they proclaimed. Therefore, when for the truth you had contested, rejoicing, to those in Hades you preached the Gospel, that God was manifested in the flesh, and takes away the sin of the world, and grants to us the great mercy.

Through the prayers of our Holy Fathers, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy on us and save us! Amen!

http://full-of-grace-and-truth.blogspot.ca/

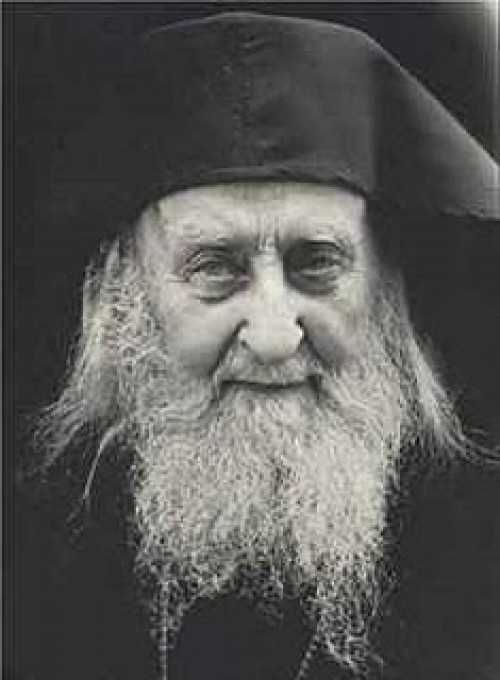

The last days of Elder Sofronios of Essex

Four days before he died, he closed his eyes and did not want to talk to us anymore. His face was radiant but not sad; full of tension. He had the same expression like when he was ministering the Devine liturgy. He would not open his eyes, or utter any words, but he would lift up his hand and bless us. He was blessing us without words but I knew that he was going away. Before, I used to pray that God should let him leave longer, just as we pray during the liturgy of St. Vasilios: “prolong the time of the old”. However during those days, when I knew he was leaving, I started praying: “My Lord, give your servant a rich welcome into your Kingdom”. I was praying using St Peter’s words, as we read it in his second letter. (2 Peter 11)

Thus I was praying intensely: “Please God give your servant a rich entry into your Kingdom and place him among his Fathers”. Then, I would call the names of all his brothers, ascetics, in Ayio Oros, whom I knew he had connections with, beginning with Saint Silouanos and then all the others. …On the last day, I went to visit him at six in the morning. It was Sunday and I was ministering the morning service, while Father Kyrillos and the other priests would minister the second service. I realized that he was going to leave us that day. I began the service at Ayia Prothesi. At seven o’clock the Hours would start, followed by the Devine Liturgy. I only uttered the prayers of Anaforas, because at our monastery we say these aloud. For the rest of the time, I continued to pray: “Lord give your servant a rich welcome”.

That service was different from all the others. When I called out: “The Holy to the Saints”, father Kyrillos came into the Sanctuary. We looked at each other; he began to cry and I realized that Fr Sofronios was gone. I asked him what time he died and I knew that he passed away during the time I was reading the Gospel. I stepped aside because he wanted to speak to me and he said: Give the Holy Communion to the faithful and then announce that Fr Sofronios has passed away , then minister the first Trisagio; I will also do this during the second service. Thus, I took the Holy Communion myself and then offered it to the faithful. Then I finished the service. I still do not know how I managed this. Afterwards, I went out of the Sanctuary and told those present: “My beloved brothers, our Christ, our Lord, is the wonder of God in all generations of our times, because in His words we find salvation and a solution to every human problem. Now we must do what the Devine Liturgy teaches us: to give thanks, to pray and to plead. Thus, let us thank God because he gave us such a Father , and let’s pray for his soul. “Blessed be our Lord” and thus I began the Trisagio.

We placed his body inside the church because the tomb had not been built yet. We allowed his body to remain uncovered for four days and we were constantly reading the Gospels from the beginning to the end, and then again, as it is customary to do when priests have passed away. We continued with several Liturgies, and he was there in the middle of the church for four days. It felt like Easter! It was such a wonderful and blessed atmosphere! No one came into hysterics, everyone prayed with inspiration.

I have a friend, Archimindrite, who used to spend several weeks at the monastery during the summer, Fr Ierotheos Vlachos, who wrote “A night at the desert of Ayio Oros”. He is now a Bishop of Nafpaktos. He arrived as soon as he learnt that Fr Sofronios was gone. He felt the same veneration and said to me: “If Fr Sofronios is not a Saint, then there are no Saints”.

It so happened that some monks from Ayio Oros were present as well, because they had come to see him but did not see him alive. Fr Tychon from Simonopetra was one of them. Every time Greeks would visit England for medical reasons, they would come to the monastery so that Fr Sofronios would bless them; many had been cured this way. During the third or fourth day of his passing, a family of four arrived at the monastery. They had a child of thirteen. He had a tumor in the brain and his operation was scheduled for the next day.

Fr Tychon said to me: “These people are very upset because they came and did not find Fr Sofronios alive”. Why don’t you read some prayers for the child?”

I said to him: “Let’s go together. You read from the book and we will read some prayers together at the other Chapel. We did just that and at the end Fr Tychon said to me: “You know something? Why don’t you pass the child under Fr Sofronios’ coffin? He will be cured. We are messing about reading prayers”. I answered that we couldn’t do this, because people would say that as soon as he had died we are trying to promote his sanctification. “You do it”, I said. “You are a monk from Ayio Oros. No one will say anything”.

He took the child by the hand and passed him under the coffin. The next day he was operated upon and the doctor found nothing. He closed up the brain and said: “It was a wrong diagnosis. It was probably an inflammation”. A Greek doctor was also accompanying the child and was carrying the x ray documents, which showed the tumor. He said to them: “I am sure you know very well what this ‘wrong diagnosis’ means”.

That child is now 27 years old and in a very good health.

Archim. Zacharias

http://agapienxristou.blogspot.ca/2013/08/the-last-days-of-elder-sofronios-of.html

So Your Child Wants to be a Monastic?

The following talk (slightly condensed) was given [in 1984] at the Saint Herman Winter Pilgrimage in Redding, California.

I should like to ask you to think of something you may not have considered before, How would you feel if your son or daughter expressed the desire to enter a monastery? You may be Orthodox, and very devout; you may he diligent in attending services and reading spiritual books; you may have tried your best to raise your children in an Orthodox manner; you may even admire monasticism. Nonetheless, how would you really feel?

We live in a time and society quite different from Greece and Holy Russia, where monasticism was a visible and acceptable part of life. It was not uncommon for entire families to make pilgrimages to monasteries. Few people today, however, have any significant exposure to monasticism and it is little wonder that in our un-Orthodox and even anti-Christian society, the very thought of one’s child becoming a monastic can seem very threatening.

There are a number of reasons one can give for such a reaction. Lack of familiarity breeds fear. Not a few people imagine monasticism to be very grim and even inhuman. They may envision their child locked behind a grating and subsisting for the rest of his or her life on bread and water. The other extreme is an equally- erroneous view of a romanticized spiritual state in which the child spends his days floating above the ground in an exalted state of endless holiness. In both cases it is imagined that entering a monastery presupposes leaving behind the human race. The reality of the monastic life is a far cry from either of these extremes. Your son or daughter—who is always late, leaves socks and soda bottles everywhere and is generally infuriating–will not turn into an instant anchorite. Anyone who leaves the world for the monastery brings all of his weaknesses and defects with him. He may learn to overcome some of them; others he will have until bodies, In any case, if your child becomes a monastic, he or she will not be living without human warmth and human relationships, and in spite of everything, you will still recognize them as being one of your own progeny.

Whatever your initial reaction to the issue of monasticism and your child, it depends to a great extent on how you as a parent view the Orthodox family and your position as an Orthodox individual in the contemporary secular world. Surrounded as we are by worldly standards and a materialist culture, we forget that Christ calls all of His followers to separate themselves from the world: Be not of this world. This is the trumpet call of monasticism. With this understanding, you should be more ready to peacefully acquiesce to the son or daughter who has found it in his heart to answer this call by taking upon himself the monastic yoke.

We are, however, the unfortunate products of our fallen nature, and it is rare that even a pious Orthodox parent is thrilled to hear that their offspring desires to enter a monastery. More often there arise some very strong reactions in the heart which, however innocent and well-intentioned, are nonetheless aspects of our fallen emotional and psychological nature – and a sad reflection of our un-Orthodox background and environment. With this in mind we can examine some of the emotional responses which this issue so often evokes.

Verbally, the various emotions stem from the pivotal question, “Why?” Why does anyone leave the world to enter a monastery? If the reason is legitimate, it is because in spite of all his failings and weaknesses, your child loves God more than anyone or anything in the world–more than the life you helped shape him for, more than his automobile, more than the school to which you were going to send him, more than his family… And here the very natural feeling of jealousy arises. As parents you may endeavor to replace God as being central in your child’s affections and persuade him to forsake monasticism, If you succeed, you will only make the child unhappy, and if you fail, you’ re going to feel very hurt.

Secondly. you may feel estranged or shut out from your child’s life. If your daughter goes to a monastery, and it’s a life you have not shared, you may feel you can’t relate to her. If she married, even if she moved a thousand miles away, you would very likely feel that you were still more a part of her life than if she became a nun and lived 50 miles away. A married daughter would still need advice on how to cope with the children’ s illnesses or how to manage a tight budget. On the other hand, if she were in a convent, you could hardly give her advice on how to do Matins, and even if you are Orthodox, you might feel emotionally adrift and very awkward with this suddenly foreign someone in black whose life is so different from your own. Then there is also the fact that most parents look forward to being grandparents, this is a big issue, especially with mothers.

You may feel threatened. You spend your whole life nurturing the well-being of your children: you feed them and worry over them; you help them to discover their abilities and you encourage them to develop their talents. Perhaps your son is a natural musician or your daughter a born lawyer, and you spend your life supporting them–emotionally and financially–and preparing them to be successful in the world. And after all these years of effort and anxiety, they suddenly decide they want no part of it, they don’t want the world, nor the life that you envisioned for them. This can be a very threatening and painful revelation. Very often parents feel that in rejecting the world, their child is also rejecting them. This is not necessarily true at all, but this feeling sparks most of the disputes between parents and their children over the issue of monasticism. Here also parents may feel they have failed in some way in their raising of the child, that he or she should choose such an “aberrant” path in life. This is also a painful thought.

The rather heated emotions which may arise over the issue of monasticism and one’s child frequently result in a barrage of reproaches. The following examples are not in the least hypothetical; they come from a list of actual remarks made by real mothers and fathers, some of whom consider themselves to be devout Orthodox. Their responses illumine the essence of the dispute as it is felt in the heart of those who are Orthodox and yet live in the world. They’ve said that we are not taking responsibility for ourselves; that we are just leaning on someone else so as to avoid having to make our own decisions. They say that if we love our neighbor we should be working to improve society and not dropping out of it into some euphoric dream. We often hear that monasticism is mere ostentation, some kind of fake spirituality: “Why don’t you stick it out in the world like the rest of us, where you have to deal with real life and real problems?” They say monasticism is selfish, egocentric, it divides and ruins the family; monasticism is “financially unstable”: What about your future security? Why don’t you just get a good job and send them all the money?…

While these remarks are quite varied, there is a common denominator, and that is worldliness. They are all rooted in a very worldly orientation. It is the complete and absolute rejection of this perspective on the part of the monastic aspirant which often makes the dispute between parents and child so violent, Although perhaps unconscious, the parents’ message underlying all this is: Conform yourself to the world; fit in; get a secure job; settle down; do what everyone else does…; spirituality is fine, but there’s no need to be extreme. We have already seen, however, that Christianity is otherworldly; by its very notate it is extreme: if you lose your life you shall gain it; if you try to hang onto it you will lose it; God became man that men might become gods. What could be more extreme?

Seek ye first the kingdom of God

Orthodoxy is the means by which we ascend unto God, through surrendering our own ego and self-will. Orthodoxy means war–against one’s fallen nature, against the devil, and against the world. This applies to all Orthodox Christians. Even those who live in the world–who have children and hold jobs–are required to keep themselves in some sense apart from the world. And there can be no compromise. The world is not and cannot be our home, and whether we choose to marry Christ or an earthly spouse, we can in no sense marry’ the world. We see, however, that it is precisely this desire–to have both God and the world–that is at the rooter the conflict evoked by the child’s entrance into monasticism. Experiencing their own reaction to the child’s rejection of the world may make the parents realize, perhaps as never before, their own attachment to the world, and how unwilling they are to sever themselves from the values and desires of the anti-Christian society in which they live.

It is especially difficult to struggle against the accepted view of the family which in this country has received a pseudo-religious status; youngsters are often all but worshipped as gods by their parents who see them as fulfilling their own egos. This is not Orthodox; it is, in fact, very destructive of our Orthodoxy which teaches that children are not the possession of their mothers and fathers: they are not playthings of their parents’ imaginations. Children are given by God for a time that they may be raised up in the knowledge of Him, and after that He summons them as He will. The duty of parents is not to prepare children to settle comfortably in the world, but to shepherd their souls, to prepare them to battle against the fallen world. Those who choose to fight in the front lines are those who hear the monastic calling. If your child wants to enlist in that war, he will swear before God and man that despite his sinfulness and frailties that overwhelm him at every hour of the day, he cannot find rest apart from God.

If such is the inclination of your child, do not hold him back, however logical your reasons For wanting to do so may be. If the desire for monasticism is simply a fanciful notion, they will find out soon enough, and nothing will be harmed by their trying. If, however, such a desire has indeed been planted by God as a means of their achieving salvation, don’t thwart it by trying to persuade him first to finish school or experience life in the world. Bring to mind the countless number of monastics, both men and women, whose spiritual legacy has so greatly enriched our holy Orthodox Church. If your child has the desire and determination to follow in their steps, however weakly, bless him, let him go. And may this blessing be also unto your own salvation and that of others.

What Causes Coldness in Prayer? - Saint Theophan the Recluse

.jpg)

Many will blame the prayer or their prayer rule when they experience coldness in prayer. Saint Theophan says, "If prayer is going poorly is not the fault of the prayer but the fault of the one who is praying." He points out that it is our haphazardness in our approach to prayer that is the most common problem. For me, this occurs when I am in a hurry. I want to rush through my prayers so I can get on with a busy day. When this happens my prayer become routine and my heart is cold in relation to the words of the prayer and it is no longer prayer. It becomes simply another task for the day.

What do we do when we experience this coldness in prayer? Saint Theophan says simply, "reprimand yourself and threaten yourself with Divine judgment."

When we are in a hurry we are making God secondary in our life. Most of us spend very little time in prayer in relationship to all the other activities of our life. We really do not have any excuse for trying to rush through our daily prayers. We need to shame ourselves for this. No one else can do this for us. Our haste only leads to a compete waste of time. Prayer without feeling is not prayer.

Saint Theophan outlines what some people do in regards to prayer.

They set aside a quarter of an hour for prayer, or half an hour, whatever is more convent for them, and thus adjust their prayer time so that when the clock strikes, whether on the half hour or hour, they will know when it is time to end. While they are at prayer, they do not worry about reading a certain number of prayers, but only that they rise up to the Lord in a worthy manner for the entire set time. Others do this: Once they have established a prayer time for themselves, they find out how many times they can go around the prayer rope during that period... There are others who get so accustomed to praying that the times they spend at prayer are moments of delight for them. It rarely happens that they stand at prayer for a set time only. Instead, they double and triple it. Select whichever method pleases you best. Maintain it without fail... A large part of my daily prayer rule is reciting the Jesus Prayer. For a while I would set a set number of prayers to accomplish my rule. I found myself rushing to complete them in a shorter and shorter time. I even came up with innovative ways to say them faster. I finally realized that I was not praying when I did this. Prayer was not about numbers but about a arm feeling in the heart in an intimate relationship with God. So I changed my practice to one based on a set time. Now I concentrate only on the words of the prayer, my Lord and Creator, and not on how many times I am repeating the prayer. This allows for a varied pace depending on your current state and allows for some spontaneity in your prayers as well.

Reference: The Spiritual Life, pp 287-289

Struggle for Christ ( Elder Joseph the Hesychast )

Without a struggle and shedding your blood, don’t expect freedom from the passions. Our earth produces thorns and thistles after the Fall. We have been ordered to clean it, but only with much pain, bloody hands, and many sighs are the thorns and thistles uprooted. So weep, shed streams of tears, and soften the earth of your heart. Once the ground is wet, you can easily uproot the thorns.

Elder Joseph the Hesychast